Osaka Expo 2025 - A Tale of Two Pavilions

- FHA

- Jul 30, 2025

- 8 min read

Updated: Aug 1, 2025

Growing up during my youth in the States, I consider myself part of a generational milieu for whom international travel was not a frequent occurrence. This changed somewhat in my twenties, when I was in Kuala Lumpur, working in an architectural office known for being 'international'. It was also the rise of magazines like Wallpaper*, flaunting their jet-setter lifestyles, as if there was something wrong with you if you did not have access to this world. I wouldn't want to say it opened my eyes, (as I continue to believe that enlightenment is a choice we should all have agency over,) but it did upend my expectations over what life could look like.

Within the insular world of architecture, something that seemed almost a rite of passage among my colleagues back then was having visited an Expo. Like a contemporary version of Lord Byron on one of those Grand Tours of Europe.

In my time, this would have meant you've seen MVRDV's stacked sandwich tower or Peter Zumthor's glorified lumber yard, both at Expo 2000 in Hanover. I was (and still am) perfectly content seeing and studying those pavilions second-hand, via books and the internet. But I wouldn't be entirely truthful if I did not acknowledge just a tinge of envy at not being able to experience them in person.

I generally prefer to stay well away from places that are to be the stage for a global event. You certainly won't find me visiting any country while it hosts the World Cup. Even in 2012 when the Olympics were in London, I didn't want to go anywhere near Stratford. (Although I remember the West End being a strangely blissful oasis of calm after residents were advised to stay away.) But, on this occasion, the stars just happened to align with our latest visit to see family. Since we were going to be in Japan anyway, we might as well Expo, this year in Osaka.

Beyond my understanding of these as temporary architectural theme parks, my previous perception of such events were mainly coloured by the remnants of an underused park in Queens or the baseball team that used to be in Montreal.

I only more recently clocked that the word expo is an abbreviation of the word exposition. And I had to look that word up. If you don't know what it means, you should look it up too. (For this, I have to thank a philosophical Tanzanian man on an episode of Joanna Lumley's travels in Zanzibar.) I wonder what percentage of people attend Expos not knowing the origin of that word?

We attended not too long after the opening day. Being in Japan, it had all the dignified aplomb and unalloyed enthusiasm that one can expect from Japanese-run events. And it was huge. We were just there for one day but only saw a fraction of it. (If I lived in Osaka, I would definitely make use of a multi-day pass to visit during non-peak times.) So we needed to go in knowing which of the pavilions were must-sees for us. With limited information at the time, we were steered by two tips. The first, Japanese telly - it was said that if you could only see one pavilion, make it the USA one. Images of the underside of a rocket launching into space cemented this in the mind of my son - so that was one decided. The second, was from one of those design websites that I just can't keep up with anymore - Dezeen. Of the ten pavilions they highlighted, the Uzbekistan one visually piqued my interest for its architectonic expression. My review and reflections thus follow -

The USA pavilion was located very close to the main entrance (the one nearer to the extended Metro station). Two projecting black wedges spread themselves open like limbs. Within this vortex was a cube, clad in reflective material, which seemed intended to appear mysteriously 'floating', like a permanently gift-wrapped Apple store. Broad LED screens on both sides of the wedges bombarded you with visuals of Americana, with the floating cube blurrily merging reflections from both sides. This open triangular court served to draw you in from the outside, then blocked out the surrounding visual static, while keeping you occupied like a drive-in theater as you waited in the (often long) queue.

After passing underneath the cube, when your group in the queue was up next, you got to go inside. And when you are inside, you are only inside. As a scripted experience, it was not so much a space as it was a sequence. With stories of Fulbright scholars and Thanksgiving dinners, innovation and sightseeing, and finally culminating in a large rectangular room for the rocket launch into outer space. And yet, I was completely unprepared for how cute it would all be. Not the building, which now barely registered as background, but the storyboard.

Cue in, Spark, the animated mascot of the USA pavilion - a squishy star that would bounce around from one screen to another, singing a catchy tune, sung by the voice of some nubile starlet with cheerful innocence (- think a young Miley Cyrus before her bawdy phase): "Together... together... just imagine what we can (fill-in-the-blank), together..." I'm not sure the best imagineers at Disney could have come up with better. It was almost enough to make me momentarily forget the jingoistic times we live in. Even if I knew a lot of it was naive, if not disingenuous, it didn't stop me wanting to believe. At the end of it, they could have slopped that Kool-Aid into a trough and I would have been happily slurping it all up.

If there was a materiality to this pavilion, one would hardly know it. The architecture, with its subservience to electronic screens, seemed to have more in common with a sports stadium or a big-box electronics store. Upon exiting, architects would probably recognise the large room of the rocket launch to be the hitherto mysterious floating cube. And kudos to the designers for making the level change feel virtually unnoticeable to get up into the cube from one wedge and out the other. But alas, would most people notice? Like the arrivals hall of an airport, more familiar to the back of our heads, we move on to the next thing.

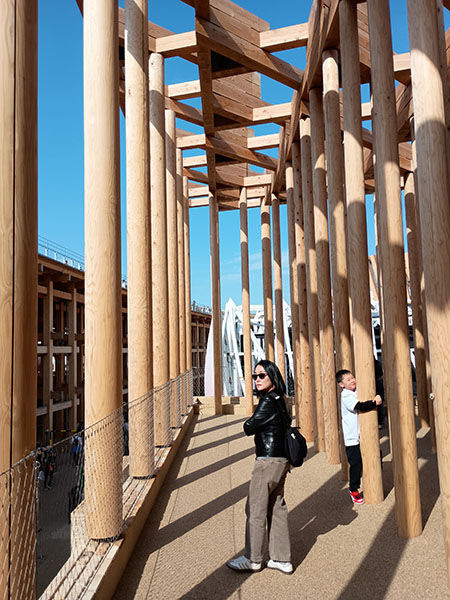

We saw a handful of other nearby pavilions, but the Uzbekistan pavilion was a ways away. And so we hopped onto this Expo's elevated ring road expressway, which is literally a circular ring. Made of gargantuan timbers, this monument to the mortise and tenon encapsulated how the Japanese love to breathe new life into ancient traditions. (At the time of this writing, it remains undecided how this record-breaking quantity of wood will be reused or repurposed... Stay tuned?)

As we got closer to our destination, we paused at the edge of the elevated ring. Standing as we were, atop a constructed forest of chunky chopped-down trees, we looked down at another, albeit smaller-scaled, constructed forest of chunky chopped-down trees. By this time, queue fatigue had started to set in, so we stood above the line of people at the Uzbekistan pavilion for a moment to gauge how long it would take to get in, as the stops and starts weren't very frequent. Eventually, I just had to wail that ultimate rally cry of the FOMO warrior, "We're never gonna be here again," and marched my family to get off at the nearest exit to hurry up and start waiting.

Occupying the entirety of its triangular plot, the Uzbekistan pavilion was an exercise in geometrical repetition, not unlike what one may associate with the decorative patterns of Islamic art. From a sparse single storey plinth of brick, rose a dense triangular grid of tall timber pillars, supporting a denser triangulated brise soleil above. I'm sure many hours were spent getting the sizing and spacing of these timber elements to be just right, with plenty of sunlight analysis to ensure adequate shadow cover - a consideration which would not be lost on an oppressively sweltering Japanese summer's day. This entire composition was in the naturally monotone colour of the desert, with matching sand scattered about the grounds for effect.

When it was our turn to go inside, (another tour in grouped bunches,) we were led into the darkness of the brick plinth, the hollowed out podium before the main event. And it stayed dark throughout, the cavern lit mainly by ice-sculpture-like glowing display models representing Uzbekistan's latest planned innovations, whether in sustainable energy or transport. We were then all ushered into a circular chamber, reminiscent of those spinning amusement park rides that pin you to the wall of a barrel with centripetal force. After some abstractly projected videos, the door was reopened and we were spilled outside into the forest of timber pillars. The cylinder was in fact, a lift.

This was what I had waited for. To walk within those fabricated woods, to feel the huggable proximities, to move between light and shadow, to breathe in the smell of the Japanese cedar. The beauty of it did not disappoint. On reflection, I can see the intent of the designers on recreating the journey of seeds, from their nascent gestation buried in the earth, to their vertical sprouting into a collectively merged canopy. But, for all its material poetry and elegant proportions, I regret to say the experience left me feeling empty.

In addition to being a grown-up architectural playground, an Expo is also a form of tourism for the host city. This is particularly pertinent given the weakness of the Yen, currently at a level unfamiliar to me in my lifetime. (For better or worse, Abenomics seems to have done its job.)

At the risk of orientalising Uzbekistan as a lesser-known other, one has to admit that it is not a mainstream destination like Italy or France. Images conjured up by the old Silk Road have a powerful allure, but I think their handling of it erred too far on the conceptual side. I don't want to take any admiration away from their country's planned innovations, such as high speed rail. But remember, this pavilion is in Japan - birthplace of the bullet train and countless other things you didn't know you needed. With its sparse presentation, visitors to the Uzbekistan pavilion, guided solely by Japanese staff, were left with no idea of what an Uzbek person looks like, nevermind what clothes they wear or what music they might listen to... And what do they eat? What does their food taste like? What do I have to do to get some plov around here?

Meanwhile, the USA pavilion had live jazz and barbeque - you couldn't get the stars and stripes out of the air if you wanted to.

My brother, who is very talented at what he does, (I can't quite put a name to it but it is something to do with film-making and animation,) once asked me if I ever considered working in set design. I replied that I hadn't thought about it. With images of flimsy spaghetti western facades rolling like tumbleweeds in my mind, I furtively felt that would have been beneath me. I can hear in the background the mutterings of my contemporaries, "Real architecture affects how people live!" Such is the haughtiness of our profession.

Trained as I had been, the younger me aspired to the 'high art' of my trade. I was armed with the belief that it is the form which controls the content, much like an actor can control a scene through their delivery. But what is an actor without a good script? Similarly, as a vehicle for capturing the imagination, architecture can only go so far.

Take Thanksgiving. I think it is a travesty that the rest of the world intractably labels this an American holiday, rather than something which can be universally adopted. In the spirit of Expo, why should Thanksgiving be the exclusive preserve of Americans? Why can't we all have a Thanksgiving too? It would definitely ease some pressure off the overcooked timebomb in this country that is Christmas. For underneath the gluttony, the bickering amongst family and the marathon of NFL games, Thanksgiving is at once a profound practice as well as a powerful idea. I can remember from my college days, how my family would happily host my international friends, when they didn't have a nearby home and family to go back to. Can architecture honestly hope to do anything that would top the grace of this neighbourly gesture?

I say it cannot. And I am ok with this. For the built environment is at its best when it makes ordinary people the star. Perhaps this is the humble pie we as a profession need to eat.

Now, where do I have to go to get some good plov?

Comments